Tundra Comics cracks me up. Second opinion! Second opinion!

Scala, Java, Unix, MacOS tutorials (page 18)

| A top-rated programming book on Amazon | |

|

Agile Estimating and Planning |

I have no idea how it works, but every once in a while you’ll have dreams that come true. For example, a few years ago one of my nieces got married, and even though I didn’t go to the wedding, two nights before the wedding I had a dream of a photo that was taken, and what I saw in the dream was exactly the same as the photo, even though I have never been to the place where they were married or seen photos of the place.

(Actually there was a difference: On the far side of each row of people I saw some relatives who passed away many years ago. They were also dressed in suits and dresses.)

Then a few weeks ago I had a dream that Dr. Ruth passed away, so when I saw that she actually passed away on July 12, 2024, I asked my wife, “Didn’t you tell me that Dr. Ruth died a few weeks ago?” She said no, she didn’t say anything like that, and then I remembered that that happened in a dream.

This doesn’t happen very often, but I used to make a note of such things because I thought it was fascinating. These are just two that I can remember off the top of my head.

“Most people treat the present moment as if it were an obstacle that they need to overcome. Since the present moment is life itself, it is an insane way to live.”

~ Eckhart Tolle

Without any introduction or discussion, here’s a little Scala script I just wrote to read in a text file that contains stocks symbols, with one symbol per line, along with some blank lines; then convert those symbols to comma-separated output (CSV format) that I print to STDOUT:

I just had this problem in Scala where I wanted to concatenate two corresponding multiline strings into one final multiline string, such that the elements from the first string were always at the beginning of each line, and the lines from the second string were always second. (When I say corresponding, I mean that the two strings are of equal length.)

That is, given two Scala multiline strings like these:

If you want to get a value out of a Scala Option type, there are a few ways to do it. In this article I’ll start by showing those approaches, and then discuss the approach of using the fold method on an Option (which I’ve seen discussed recently on Twitter).

1) Getting the value out of an Option, with a backup/default value

As a first look at getting values out of an Option, a common way to extract the value out of a Scala Option is with a match expression:

Sister 1: “What about that cute guy I met? Condom Man.”

Sister 2: “Yes, that’s how he likes to be known.”

Sister 3: “Condom Man? Sounds like a superhero.”

~ from the movie, Must Love Dogs

Two sisters talking in the movie, Must Love Dogs:

“So can I ask you a question?”

“No.”

“You never would have left Kevin, would you?”

“If he hadn’t ... left me? No, I don’t think so.”

“But you weren’t really happy.”

“Well, I figured that was the life I picked, so I had to make the most of it. I’m not even sure I deserve a new life now. Sometimes I think that was supposed to be my one chance and I blew it.”

“Where did we get the bad attitudes?”

“The nuns?”

“Yeah, that works. Let’s blame the nuns.”

I need your grace

To remind me

To find my own.

~ a favorite line from the song, Chasing Cars

“Remember that you are the Witness only ... even for a moment, do not think that you are the body.”

~ Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj

If you ever want to use ImageMagick to crop a bunch of images that are in one directory, I can confirm that this command crops all the JPG images in the current folder while creating new JPG files with the new name shown:

I saw this 19th century ocean painting on Flipboard. The color/translucence of the water is incredible.

As a quick note, here’s a Scala function to generate a random integer value that will be in between the input min and max values:

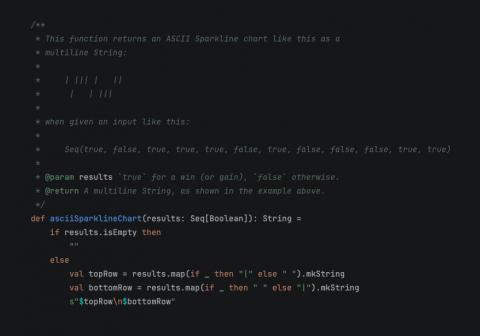

As a brief note today, here’s a little Scala application that reads an HTML file, parses it with JSoup, and then I select all of the elements with the CSS selector shown. After that, I use some Scala goodness to read all the text values of those elements, see if there is a "W" (win) or "L" (loss) character there, convert that to a Seq[Boolean], and then generated an ASCII Sparkline chart based on those results.

Note that the desired CSS selectors look like this in the HTML:

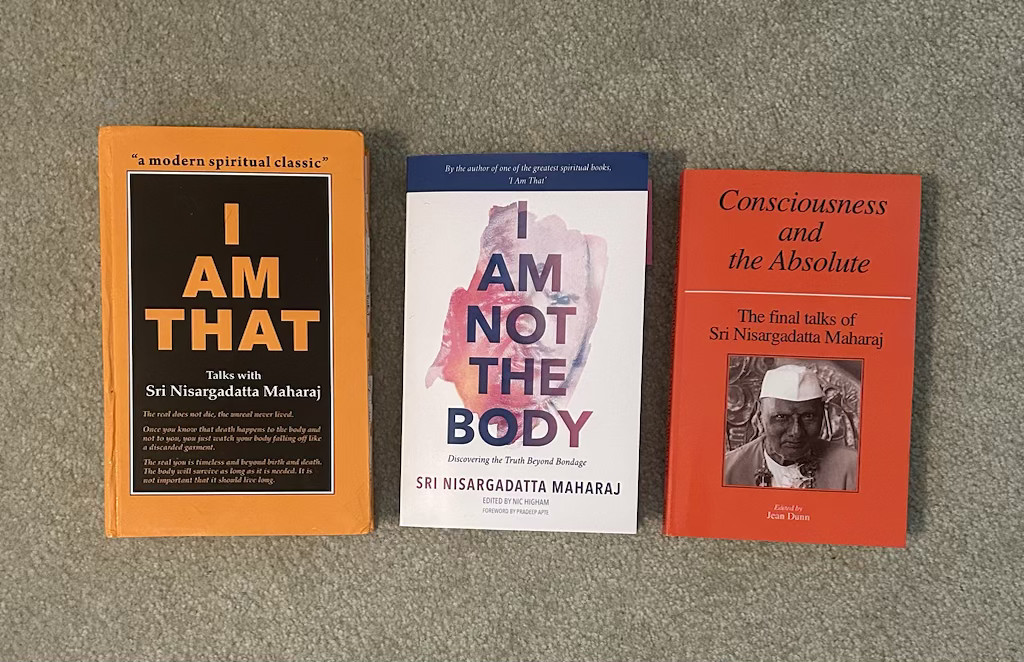

If you’re interested in Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj’s best books, I share my opinions in this blog post. And just to confirm that I have bought the books I’m talking about, here’s a photo of them:

UPDATE: The latest version of this code is at github.com/alvinj/TextPlottingUtils.

Creating an ASCII version of a Sparkline chart — also known as a Win/Loss chart — in Scala turned out to take just a few lines of code, as shown in this source code:

Creating an ASCII version of a Sparkline chart — or Win/Loss chart — in Scala turned out to take just a few lines of code, as shown in this photo.

As I mentioned previously, the Neotype library is a nice improvement over the verbose Scala 3 opaque type feature. This little example begins to show how much better Neotype is than opaque types, where opaque types require more boilerplate to implement less functionality:

//> using scala "3"

//> using lib "io.github.kitlangton::neotype::0.3.0"

import neotype.*

// [1] Opaque type:

opaque type Username = String

object Username:

def apply(value: String): Username = value

// [2] Neotype:

object Password extends Newtype[String]:

override inline def validate(input: String): Boolean =

input.nonEmpty && input.length > 2

@main def NeotypeTests =

val u = Username("Alvin")

println(u)

val p = Password("12")

println(p)

| A top-rated programming book on Amazon | |

|

Agile Estimating and Planning |