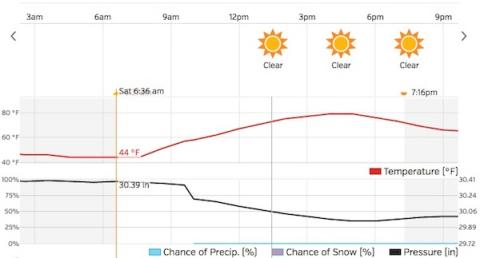

I think last night was the first night this autumn/fall that the temperature dropped down to 40 degrees in the Boulder, Colorado area. (Imagine from wunderground.com.)

Scala, Java, Unix, MacOS tutorials (page 187)

[high school]

Teacher: Do you have your homework?

Ryan Lochte: I was murdered last night.

(which reminds me of,

“One time I exaggerated so much I died.”)

Java FAQ: How can I use multiple regular expression patterns with the replaceAll method in the Java String class?

Here’s a little example that shows how to replace many regular expression (regex) patterns with one replacement string in Scala and Java. I’ll show all of this code in Scala’s interactive interpreter environment, but in this case Scala is very similar to Java, so the initial solution can easily be converted to Java.

“95% of soy products in the United States are genetically modified, and do not have to be labeled as such.”

From the book, The Wahls Protocol

“What disturbs the mind? Wanting, wanting, wanting everything.”

~ Swami Satchidananda

“To me, the most important part of a program is laying out the data structure.”

Using Akka logging is a great thing, until you need to turn it off. In short, to disable Akka logging, you need to create a file named application.conf in your SBT src/main/resources folder, and set the loglevel to “OFF” in that file, like this:

#

# see http://doc.akka.io/docs/akka/snapshot/general/configuration.html

#

akka {

# options: OFF, ERROR, WARNING, INFO, DEBUG

loglevel = "OFF"

}

I show the other log levels in the comments in that file, but setting it to OFF disables Akka logging.

When I refer to Akka logging, I’m referring to logging when you have an Akka actor that extends ActorLogging.

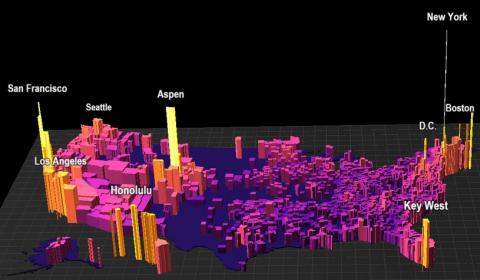

This map from this medium.com article shows the most expensive housing markets in the United States. (Which helps to explain why some seemingly average-looking homes in Colorado are so expensive.)

As a way of demonstrating how to write code with Akka, Scala, and functional programming (FP), I started creating a new project this weekend. I named it Aleka, because it may eventually be like Amazon’s Echo/Alexa, written with Akka (and Scala).

(I suppose a better name might be “Ekko,” after Echo, but I have a niece named Aleka, so unless she objects, this works for me.)

In the Scala Standard Library, a Future is a data structure used to retrieve the result of some concurrent operation. This result can be accessed synchronously (blocking) or asynchronously (non-blocking).

~ from the akka.io docs

(For more information, here’s my Scala Futures example.)

Shortly after a dream in which people were trying to kill me with guns that shot carrots (to which I replied, “I get the metaphor, can we move on?”), I had another dream in which a woman picked up a stone, turned it over, and showed it to me. A burning image of Jesus on the cross was on this other side.

Skipping over some stuff, it eventually reminded me of this quote: “Jesus said, ‘The Kingdom of God is inside you, and all around you, not in mansions of wood and stone. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift a stone, and you will find me.’”

(notes from a dream on september 3, 2016)

Last night I had a dream in which a woman picked up a stone, turned it over, and showed it to me. A burning image of Jesus on the cross was on this other side. Skipping over some stuff, it eventually reminded me of this Gospel of Thomas quote: “Jesus said, ‘The Kingdom of God is inside you, and all around you, not in mansions of wood and stone. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift a stone, and you will find me.’”

This morning this makes me think of the song, Minutes to Memories, by John Mellencamp. (I used to link to the video on YouTube, but it has been removed.)

“Purity makes the job of understanding code easier.”

After Lovely Rita, the song I’ve listened to the most this past week is Breaking the Girl, by the Red Hot Chili Peppers:

FWIW, I don’t think I’ll be posting any new chapters for my “Functional Programming in Scala” book this weekend. I had a bad episode at the grocery store this morning (I started shaking, dropped a half-gallon of milk, it exploded and flew everywhere), so I’m back to seeing doctors again. I’ll post an update here as soon as I’m able to release any new book chapters.

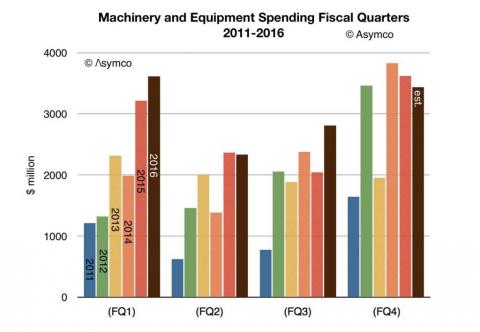

This techpinions article shared this image that shows Apple’s spending on equipment and manufacturing. A key line from the article: “However, Apple stands above most in this area because, if they can’t find the right equipment to make a product, they actually invent and/or create the equipment, either with the help of a partner or they do it themselves.”

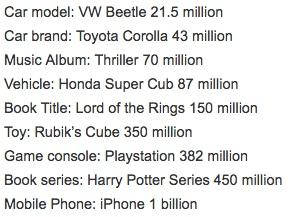

In only nine years, Apple’s iPhone is the best-selling product of ever. (Info from asymco.com.)

(Note: I don’t know if most Bibles are sold or given away, but I suspect they are really #1.)

A fun thing about looking at different programming languages is that you get to see the unique features of each language. For instance, some people don’t like Lisp because of all of the parentheses, and then Haskell seems to counter that by saying, “Hey, here are a couple of ways to get rid of parentheses.”

Haskell’s $ operator

One of the approaches Haskell uses is the $ function, which is called the function application operator. As an example of how it works, imagine that you want to calculate the square root of three numbers. This first approach is intentionally wrong because it calculates the square root of 3, then adds that to 4, then adds that to 2:

let x = sqrt 3 + 4 + 2 # intentionally wrong

The usual way to correct this is with parentheses: you need to make sure the three numbers are added together first, before the sqrt function is applied. As with other programming languages, Haskell lets you write this:

let x = sqrt (3 + 4 + 2)

For the first 20+ years of my programming life I wrote code like that, but Haskell says, “You know what, those parentheses are kind of noisy, let’s get rid of them.” The way you get rid of them is by using $ instead:

let x = sqrt $ 3 + 4 + 2

Whoa, that’s different.

The first 50 or 100 times you see that it’s pretty freaky, but over time it grows on you. As the book, Learn You a Haskell for Great Good states, you can think of $ as being like an “open parenthesis.”

Comparing parentheses to $

IMHO, the $ is a little more attractive when you compare it to the same expression that uses parentheses. For instance, these two lines are equivalent, and the second line is a little easier on the eyes:

sum (map sqrt[1..10])

sum $ map sqrt[1..10]

The same is true of these two lines of code:

putStr (map toUpper "rocky raccoon")

putStr $ map toUpper "rocky raccoon"

Until I saw this approach, I never realized how much noise parentheses add to an expression.

Read from right to left

Here’s one more example:

let x = negate(sqrt(3 + 4 + 2))

let x = negate $ sqrt $ 3 + 4 + 2

With an expression like this, you basically read the code from right to left. That last line can be read like this:

Sum up “3 + 4 + 2” // 9Take the square root of that // 3Negate that value // -3Bind that result to x // x = -3

Because of the way it works, we say that $ is right-associative.

At the moment I don’t know how the Haskell creators came up with the

$symbol. When I read code like this it reminds me of reading Unix command pipelines, except that you read them from right to left. That makes me think that the|symbol would have been cool here.

Summary

I don’t have a major summary here, I just wanted to show a few examples of how to use Haskell’s $ operator (which is technically a function). The $ in Haskell has at least one more use that I’m aware of, and I’ll try to write about that at some point.

(Note: The examples on this page were inspired by the book, Learn You a Haskell for Great Good.)

I started an “autoimmune” diet a few weeks ago, and one thing it has done is to make my problems more consistent. This is one of my current problems: at rest my blood pressure is usually low and my heart rate is often in the 95-110 beats per minute range.

Here’s a link to five more chapters from my book, Functional Programming, Simplified.