Update 1: The next version of my book on Scala and functional programming will be released later this week.

Update 2: The price of the book will be increased to $25 on July 1, 2017.

Update 1: The next version of my book on Scala and functional programming will be released later this week.

Update 2: The price of the book will be increased to $25 on July 1, 2017.

“Erlang has single-assignment variables. As the name suggests, they can be given a value only once. If you try to change the value of a variable once it has been set, you’ll get an error.”

(“Single-assignment variables” are the same as val fields in Scala. Using them can make your code more like algebra.)

Joe Armstrong, in his book,

Programming Erlang: Software for a Concurrent World

(Scala comment added by me)

“In Erlang, processes share no memory and can interact with each other only by sending messages. This is exactly how objects in the real world behave.”

Joe Armstrong, in his book,

Programming Erlang: Software for a Concurrent World

“Processes interact by one method, and one method only, by exchanging messages. Processes share no data with other processes. This is the reason why we can easily distribute Erlang programs over multicores or networks.”

Joe Armstrong, in his book,

Programming Erlang: Software for a Concurrent World

“In Erlang (Akka), it’s OK to mutate state within an individual process (actor), but not for one process to tinker with the state of another process.”

In Joe Armstrong’s book,

Programming Erlang: Software for a Concurrent World

(with Akka notes added by me)

When my dad was my current age (and I was 20), I didn’t know it, but that would be the last time I’d see him until after lung cancer had ravaged his body. If I could have said, “Please quit trying to control my life, let me make my own mistakes, and I’ll let you know if I need any help” — and he would have agreed to that — we might have found a way to see each other again.

So, my recommendation is that if you have a dad, no matter how well you’re getting along, give him a hug. ;)

I thought it was great that you can donate any dollar amount you want to The Guardian to support professional journalism. I wrote the New York Times and Washington Post and said I don’t read their content enough to justify a subscription, and asked if I could either donate to them or use some form of micropayments, but they both wrote back to say they only offer (more expensive) subscriptions.

Update: Someone wrote on Twitter to note that these are for-profit organizations and therefore they can’t take donations. That’s not true, but even if they didn’t want to accept donations, they could offer micropayments or lower-cost subscriptions for a limited number of page views.

Scala is a great language in many ways. One great feature is that you can use it as a “Better Java” (i.e., as an OOP language), and you can also use it as a pure FP language. While some people prefer one extreme or the other (not unlike extremist Republicans and Democrats in the U.S.), I appreciate that this lets you find a “Middle Way” of using the best features of both approaches.

Well there’s a light in your eye that keeps shining

Like a star that can’t wait for the night

I hate to think I’ve been blinded, baby

Why can’t I see you tonight?

And the warmth of your smile starts a-burnin’

And the thrill of your touch gives me fright

And I’m shaking so much, really yearning

Why don’t you show up, make it all right?

(Lyrics from a favorite song of my youth,

Fool in the Rain, by Led Zeppelin)

“Two steps are required to write a good piece of code. The first step is to get the algorithm right. The second step is to figure out which sorts of things (types) it works for.”

From the “Deriving a Generic Algorithm” chapter in the book, From Mathematics to Generic Programming.

To enable a physical Android hardware device (phone or tablet) for developing and debugging your apps with Android Studio, follow these steps.

The first thing you have to do with a new Android device is to enable the developer options in the Settings app. To do this:

In Android 7, as you tap “Build number,” you’ll see it count down, which is a nice touch. When you finish with this you’ll see a message that says something like, “You’re now a developer.”

Next:

At this point your device should show up in the “Select Deployment Target” window when you click “Run app” in Android Studio. If it doesn’t show up, there is one more step you need to take on your device.

The short version of this goes like this:

(I describe this solution more in my Android File Transfer error: Can’t access device storage (solved) tutorial.)

At the time of this writing this android.com article, Configure On-Device Developer Options, wasn’t 100% clear about this process, so I wrote this article to save me some time in the future. I hope it helps you as well.

Buddha was asked, “What have you gained from meditation?”

He replied, “Nothing!” Then he continued, “However, let me tell you what I have lost: anger, anxiety, depression, insecurity, and fear of old age an death.”

Without much introduction or discussion, here’s a Scala example that shows how to read from one text file while simultaneously writing the uppercase version of the text to a second output file:

import java.io.{BufferedWriter, File, FileWriter}

import utils.IOUtils.using

object SemiStreaming extends App {

val inFile = "/Users/al/tmp/in.dat"

val outFile = "/Users/al/tmp/out.dat"

// caution: this throws a FileNotFoundException if inFile doesn't exist

using(io.Source.fromFile(inFile)) { inputFile =>

using(new BufferedWriter(new FileWriter(new File(outFile), true))) { outputFile =>

for (line <- inputFile.getLines) {

outputFile.write(line.toUpperCase + "\n")

}

}

}

}

This example uses the using construct, which I’ve discussed in other Scala file-reading tutorials on this website.

Way back in the 1990s I created some “cheat sheets” for Unix training classes that I taught. Somewhere in the 2000s I updated them to make sure they worked with Linux as well, Here then are two Unix/Linux cheat sheets I created (way back when) that you can print out if you’re just learning Linux and the vi/vim editor:

I’ve read before that practicing attitudes like gratitude and humility can help re-program the brain in a positive way. Conversely, you (or your toxic parents) can also train the neural network in your brain to tend towards negative thoughts. I thought of this when I saw this article by Annie Wood titled, How complaining rewires your brain for negativity (and how to break the habit).

Being interested in baseball, Tom Seaver, and Alaska, this article about Tom Seaver’s first game in Fairbanks, Alaska is interesting.

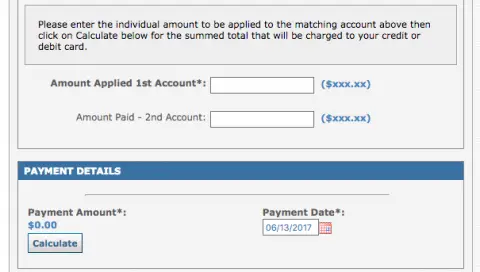

I’m sitting here writing a book on how to write better software using functional programming techniques, then I go to the Boulder Community Hospital website to pay my bill (powered by chase.com), and they don’t tell you how much you owe, you’re just supposed to type in how much you think you owe. It’s like calling Kramer on Seinfeld to get a list of movies: “Why don’t you just tell me where you want to see the movie?” *crazy*

“putStrLn doesn’t print to standard out, it returns a value — of type IO () — which describes how to print to standard out, but stops short of actually doing it.”

From the article, An IO Monad for Cats.

As a quick note, if you’re interested in using the IO monad described in this IO Monad for Cats article, here’s the source code for a complete Scala App based on that article:

import cats.effect.IO

object Program extends App {

val program = for {

_ <- IO { println("Welcome to Scala! What's your name?") }

name <- IO { scala.io.StdIn.readLine }

_ <- IO { println(s"Well hello, $name!") }

} yield ()

program.unsafeRunSync()

}

And here’s a build.sbt file you can use to run that App with SBT:

name := "CatsIOMonadExample"

version := "0.1"

scalaVersion := "2.12.2"

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.typelevel" %% "cats" % "0.9.0",

"org.typelevel" %% "cats-effect" % "0.3"

)

Running the App looks like this:

> run

[info] Compiling 1 Scala source ...

[info] Running Program

Welcome to Scala! What's your name?

Fred

Well hello, Fred!

See that article for more information. I just wanted to show a complete example, including the necessary SBT dependencies.

August, 2019 update: The Cats dependencies are now:

libraryDependencies ++= Seq( "org.typelevel" %% "cats-core" % "2.0.0-RC1", "org.typelevel" %% "cats-effect" % "1.3.1" )