Table of Contents

- Background: What is a Cons cell?

- What it might look like in Scala

- Starting to create my own Cons class

- My second effort

- Defining my nil value

- Defining Cons

- Replacing the NilCons method bodies

- Adding a toString method to Cons

- The complete code at this point

- I’d like a :: method ...

- I hope that was interesting

- See also

For some examples in my new book on functional programming in Scala I needed to create a collection class of some sort. Conceptually an immutable, singly-linked list is relatively easy to grok, so I decided to create my own Scala list from scratch. This tutorial shows how I did that.

Background: What is a Cons cell?

The first time I learned about linked lists was in a language named Lisp. In Lisp, a linked list is created as a series of “Cons” cells. A cons cell is simple, it contains only two things:

- a value (such as

1or "foo") - a link to the next cons cell

The last cons cell in a chain of cons cells links to a Nil value.

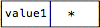

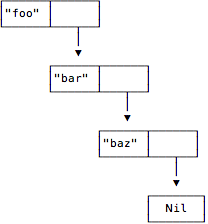

Visually, a single cons cell looks like this:

In this image I show a * character where the link would be. Here’s a short chain of cons cells, which helps to show the complete concept:

Conceptually that’s about all there is to a singly-linked list using cons cells. It’s just one cell connected to the next, which is connected to the next, and so on, until the final Nil value is reached.

What it might look like in Scala

Using only this concept, you can create a series of linked cons cells like this:

val c1 = Cons("baz", Nil)

val c2 = Cons("bar", c1)

val c3 = Cons("foo", c2)

If a Scala Cons class existed right now, that code would be an accurate implementation of what I showed in the last image.

While that’s cool, the Lisp creator(s) also defined a :: function, and with it you can create a series of cons cells like this:

val list = "foo" :: "bar" :: "baz" :: Nil

Not only is that code cleaner, it’s also legal Scala code, because the Scala List class is implemented in a way similar to what I have described. (Try it in the Scala REPL!)

While that’s all cool to know, for my purposes — writing my new book — I wanted to write my own singly-linked list class from scratch, so I pressed on and started writing my own Scala code ...

Starting to create my own Cons class

Because a cons cell consists of these two things:

- a value

- a link to the next cons cell

I initially started to create a Cons class like this:

case class Cons[+A] (value: A, next: Cons[A]) = ???

However, because I also need to create my own “nil” value to use as a way to identify the end of the list of cells, that code isn’t quite what I need. By this I mean that I need to write something like this for my custom “nil” value:

object NilCons extends Cons[Nothing]

but that doesn’t work because the Cons constructor takes two parameters. So I had to do something else.

My second effort

Because the second cell in a cons cell is essentially a pointer to the next cons cell, it occurred to me that Cons and NilCons should share some base interface. This interface should define some common behavior, but it shouldn’t require any constructor parameters.

This led me to write this interface:

sealed trait ConsInterface[+A] {

def value: A

def next: ConsInterface[A]

}

I use a generic type A here because a cons cell should be able to hold anything: an Int, a String, a Whatever. I further use the +A type parameter because the value in the cell can’t be changed. As I describe in the Scala Cookbook, this makes my collection more flexible than if I had used only A alone.

This interface is a Scala implementation of what I said earlier about a cons cell, i.e, it consists of:

- a value

- a link to the next cons cell

So far, so good.

Defining my nil value

The next thing I want to do is to make sure my custom nil value works as desired. I don’t want to confuse my nil with the Nil from Scala’s List class, so I call it NilCons. As I wrote earlier, it needs to extend the interface, so a quick sketch of it looks like this:

object NilCons extends ConsInterface[Nothing] {

def value = ???

def next = ???

}

There should only be one NilCons value in the world, so I define it as a singleton by declaring it as an object.

As for its methods, for NilCons the implementation of value and next aren’t important because they should never be called. NilCons is just used to mark the end of a series of Cons links, and the rest of my code will understand that.

That being said, I’ll show a better way to implement these methods later.

Defining Cons

Now that it looks like I have my NilCons problem solved, let’s see if I can implement my Cons class.

I know a few things about Cons. First, I want to be able to create a series of Cons cells as shown before:

val c1 = Cons('a', NilCons)

val c2 = Cons('b', c1)

val c3 = Cons('c', c2)

This code tells me a couple of things:

- I don’t want to use the

newkeyword beforeCons. This means that I either need to (a) createConsas a case class, or (b) create a companion object with anapplymethod. - The

Consconstructor will take two parameters, a value andConscell. More accurately, the second parameter must be allowed to be aNilConsvalue, which tells me that the type for the second parameter should beConsInterface, and notCons.

These thoughts lead me to this type signature:

case class Cons[+A] (value: A, next: ConsInterface[A]) extends ConsInterface[A]

Unless I have any more requirements, the Cons class doesn’t even need a body. With this current code:

sealed trait ConsInterface[+A] {

def value: A

def next: ConsInterface[A]

}

case class Cons[+A] (value: A, next: ConsInterface[A]) extends ConsInterface[A]

object NilCons extends ConsInterface[Nothing] {

def value = ???

def next = ???

}

I can write expressions like this:

val c1 = Cons(1, NilCons)

val c2 = Cons(2, c1)

val c3 = Cons(3, c2)

While that code is okay, I want to do two things:

- Replace the

???characters with some sort of code body - Add a

toStringmethod toConsto help with debugging

Replacing the NilCons method bodies

Because value and next in NilCons are never intended to be called, you can leave them defined as ???, which will lead to them exploding if they ever are called. But a better approach is to make your intent clear. I rarely throw exceptions in code, but that’s a valid thing to do here. In fact, it turns out that this is how the Nil object in Scala is defined. Copying and pasting Scala’s Nil code gives me this:

object NilCons extends ConsInterface[Nothing] {

def value = throw new NoSuchElementException("head of empty list")

def next = throw new UnsupportedOperationException("tail of empty list")

}

Because NilCons has no value, it throws a NoSuchElementException, and because it doesn’t make sense to call next on a NilCons it throws an UnsupportedOperationException. Those exception names line up very nicely with what should happen if these methods are ever called on NilCons.

Adding a toString method to Cons

Next, because I want to be able to prove to myself that my code is working as desired, I’ll add a toString method to Cons. I’ll start with this code and see if it gives me what I want:

case class Cons[+A] (value: A, next: ConsInterface[A]) extends ConsInterface[A] {

override def toString = s"head: $value, next: $next"

}

The complete code at this point

When I combine these changes with a little test App, I get this code:

package cons

sealed trait ConsInterface[+A] {

def value: A

def next: ConsInterface[A]

}

case class Cons[+A] (value: A, next: ConsInterface[A]) extends ConsInterface[A] {

override def toString = s"head: $value, next: $next"

}

object NilCons extends ConsInterface[Nothing] {

def value = throw new NoSuchElementException("head of empty list")

def next = throw new UnsupportedOperationException("tail of empty list")

}

object ConsTutorialDriver extends App {

val c1 = Cons(1, NilCons)

val c2 = Cons(2, c1)

val c3 = Cons(3, c2)

println(c1)

println(c2)

println(c3)

}

When I run that code I get this output:

head: 1, next: cons.NilCons$@14ae5a5

head: 2, next: head: 1, next: cons.NilCons$@14ae5a5

head: 3, next: head: 2, next: head: 1, next: cons.NilCons$@14ae5a5

Because I inserted the 1, then inserted the 2 before it, and finally inserted the 3 before the 2, that output looks correct.

I’d like a :: method ...

Technically this is a good start, but from an API standpoint I’d really like to have a :: method so I can write code like this:

val list = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: Nil

To do that, I need to write a :: method ...

| this post is sponsored by my books: | |||

#1 New Release |

FP Best Seller |

Learn Scala 3 |

Learn FP Fast |

I hope that was interesting

Well, I hope that was interesting. I initially planned to turned this into a series of tutorials, but I got involved in writing my book about Scala and functional programming, so I haven’t had time to get back to this.

See also

If you’re interested in learning more about Lisp, these are the best books I know:

Outside of writing Gimp plugins (which are written in a variant of Lisp called Scheme) I don’t use Lisp, but it’s an interesting language to learn about.