Using FPA, I quickly worked through several of our largest projects to determine our productivity rates, and also noted who worked on the projects, what technologies were used, along with a few other details. In short, in a few days I was able to create a database of our historical software development speed.

Ironically, there's actually a phrase in eXtreme Programming that comes into play here. (I say “ironically” because (a) XP folks will hate this technique, and (b) I laugh when XP people estimate with some arbitrary unit like “beans”. Folks, there is a more scientific way, and it doesn’t take much effort.)

When XP folks talk about making estimates, they refer to “Yesterday’s Weather.” This phrase means that if you ever want to be a weather forecaster, if you just say that “tomorrow will be just like today,” historically you'd be right 80% of the time. And when it comes to estimating software, this phrase means that you look at old projects and try to remember how long they took, and compare those old projects to the new project you're trying to estimate. To this I say, “Why trust your memory when you can have an accurate historical basis instead?”

Estimating application size

Here's a quick example of how this “back of the envelope” estimating process works:

I meet with a customer, and they describe a project to me. As we talk about the project, I make a list of all the objects (ILF's) I hear, and others that I know we’ll need. I keep asking questions until neither the customer or I can think of any more functionality. Let’s assume that at the end of the conversation I have determined that there are roughly 20 ILFs in this project.

As I showed earlier, 20 ILFs * 35 FP/ILF is 700 FPs for the effort that has been described to me. I’ll write more on this in a future blog post. The short story here is that the scope of software projects always increases, so you need to be very clear about this point with your customers:

I’m only estimating what you described to me.

So 700 FPs is the size of the application. Note that at this point it doesn’t matter if this is a thick client application, a web application, a mobile app, or even an app to run on a phone. Application size is independent of all those factors.

Estimating effort

Next, to derive a time/cost estimate from the application size, I need to know the following

- What sort of application is this? The client says it’s a web app. That’s good, we’ve built a ton of those.

- I know we’re going to use the usual Java/Spring/Hibernate/MySQL stack.

- Hours/FP. Some of our teams are faster or slower than this, but this is our average for web projects. (We’re a little slower for “thick client” apps.)

- The application may have up to 1,000 simultaneous users. This is important to know from a scalability standpoint. The infrastructure for 1B users will be much larger than 1,000 users.

There are a few more factors I need to consider, but those are the major ones.

Given these factors, I decide to use our average productivity rate of 2.5 Hours/FP, and my estimate is 1,750 man-hours of effort (2.5 * 700). Unless there is going to be a major change in the toolset the developers use, that’s the “ballpark” estimate I give to the customer.

FPA is technology-independent

One thing I want to emphasize is that FPA has nothing to do with the technology used to develop the application. As I mentioned earlier, application size has nothing to do with the technologies used to implement the solution. In the same way that “square feet” are used to measure the size of a house, FPA is used to measure the size of an application.

Just like building a house on the side of a mountain is harder than building the same house on flat land, software applications can have the same size, but different levels of difficulty. That’s where factors like scalability, platform, developers, and technologies factor in. That being said, for many business applications you’re going to use technologies you’ve used before, so the level of difficulty is basically a constant, and if you know your productivity rate for previous applications, you can apply that to future applications.

Why I like this approach

I like this approach because it’s honest, simple, and based on historical data. It also attempts to put some science into the process. Function points have proven to be a very reliable way of measuring the size of a project, and when mixed with other factors that account for the complexity of the application, can be used to yield accurate estimates. As you just saw in this case, the customer described their application to me, I used several variables that I know to be accurate, and I gave the customer a good estimate.

I know that there are other approaches to estimating software projects, and I use them as well when I have more time, but this is far and away my favorite technique for delivering early, ballpark estimates.

Uncertainty

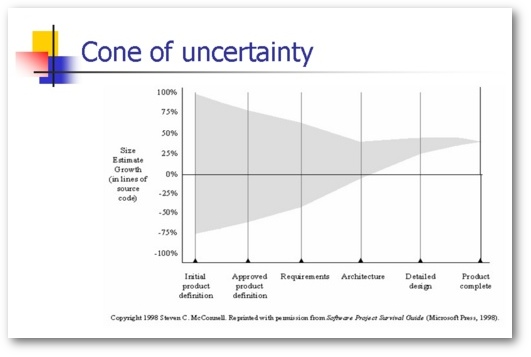

I’ll write more about the growth of software development projects in a future article, but for now I’ll just share this graph from Steven McConnell’s book, Software Project Survival Guide:

The main point of this graph is that the only time you know exactly what the client wants (and the exact application size) is when the project is delivered. Until then, you’re dealing with uncertainty. (And IMHO, a great business analyst can make a huge difference in the size/shape of that cone.)

Limitations

Like anything else, there are some limitations to this method. For instance, you may be using or even inventing a new technology. If so, this technique won’t help much. There’s always a “ramp-up” curve when learning a new technology, and you may even decide to ditch the old technology and use something tried and true.

Your approach may also be very heavy on mathematical algorithms. If so, FPA may not be for you, unless (a) the algorithms are well known and (b) you’ve done this sort of work before. Of course if you’re inventing new math, all bets are off. If you had asked Einstein in 1905 how long it would take him to discover the Theory of General Relativity, he probably would have just laughed. (He finished his work in 1916.)

A related problem is when you begin working on a project, and you realize the client doesn’t really know what they want, or the specs change. I worked for a large, international pizza chain one time, and the client’s analysts wanted to change many things. The database design changed constantly, and they never did give me a clean spec on how coupons should work. Lesson learned: You can’t count Function Points (or design a database) if you don’t know what you want, or how things work.

You also have to be careful when you begin working with a new client. The size of an application in FPs can always be determined, but a new client may be much more particular about the UI/UX than a previous client. I had this happen once where Client A had an As/400 background, and didn’t care too much about the UI, which was a web app, so we sped through the project at roughly 1.8 Hours/FP. Immediately after that, we began working on Project B, which was a Java Swing Thick Client application, and the client was very particular about the UI. This project went along at a much slower pace, nearly 3.0 Hours/FP.

Related

I just threw Function Point Analysis out here in my discussion today. If you’ve never heard of it, FPA has been around for over 30 years, and has evolved as computer programming and technologies have evolved.

For more information on FPA, see some of my other posts on this subject:

- Slides from a presentation I gave at a Borland Conference in 2004. Flipping through those will give you a nice overview of FPA.

- For the real nitty-gritty, see my popular, detailed Function Point Analysis tutorial. It demonstrates how to count Function Points for a simple application, gives you all of the definitions, and takes you step by step through the entire process.

There is also a User’s Group for FPA specialists:

A person who is certified in FPA is known as a Certified Function Point Specialist (CFPS). I held that certification for three years, and let it expire once I was satisfied that I knew what I was doing.

Summary

I hope this discussion of how to estimate software application size and provide a time/cost estimate has been helpful. I glossed over a couple of topics to help keep the discussion relatively short, but I hope it will still help. Please see the “Related” links for more information.