In today’s installation of “how to have fun with Scala,” if you want to (a) define a Scala method that takes an input parameter, and (b) that parameter has a generic type, and (c) you further want to further declare that the parameter must extend some base type, then (d) use this “bounds” syntax:

def getName[A <: RequiredBaseType](a: A) = ???

This example can be read as, “The parameter a has the generic type A, and A must be a subtype of RequiredBaseType.”

A complete Scala bounds example

As a concrete example of how using bounds works, start with a simple base type, such as this Scala trait:

trait SentientBeing {

def name: String

}

Next, extend that base trait with a few more traits:

trait AnimalWithLegs extends SentientBeing

trait TwoLeggedAnimal extends AnimalWithLegs

trait FourLeggedAnimal extends AnimalWithLegs

Then extend those with some concrete case classes:

case class Dog(name: String) extends FourLeggedAnimal

case class Person(name: String, age: Int) extends TwoLeggedAnimal

case class Snake(name: String) extends SentientBeing

Notice that Snake extends SentientBeing, but not AnimalWithLegs.

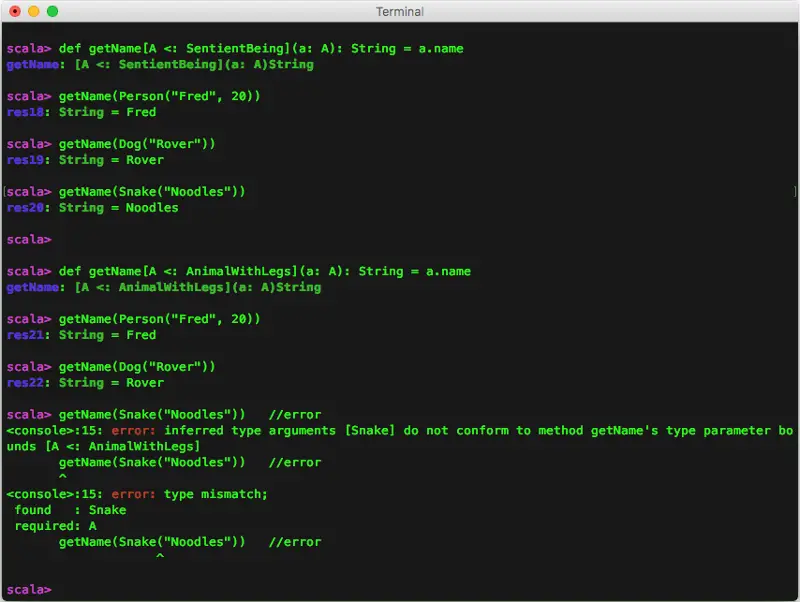

Now that you have all the types you need, define a method that takes a parameter that has a generic type that must extend some base type. To see how everything works, define it this way the first time:

def getName[A <: SentientBeing](a: A): String = a.name

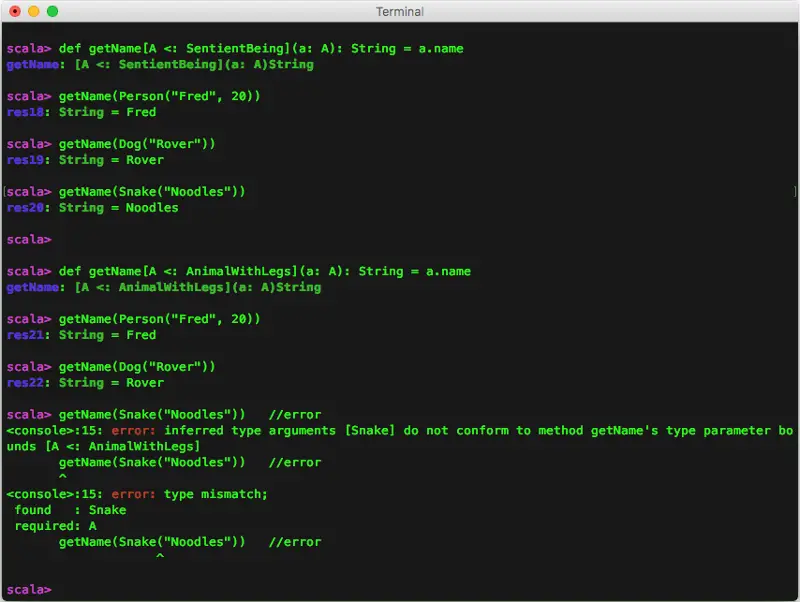

Because the base type (or “super type”) is SentientBeing, all of these calls work just fine:

getName(Person("Fred", 20))

getName(Dog("Rover"))

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

(Copy and paste those into the Scala REPL if you want to verify they work as advertised.)

Now extend AnimalWithLegs

Next, change getName so the generic type A must be a subtype of AnimalWithLegs:

def getName[A <: AnimalWithLegs](a: A): String = a.name

Now, when you run the same three method calls again, you’ll see that the Snake example fails because it doesn’t extend AnimalWithLegs:

getName(Person("Fred", 20))

getName(Dog("Rover"))

getName(Snake("Noodles")) //error

Here’s what the two sets of getName examples look like in the Scala REPL:

(Right-click that image and select “View image” to see it larger.)

The Scala “type parameter bounds” error

As shown, the second Snake example results in this error message:

scala> getName(Snake("Noodles"))

<console>:15: error: inferred type arguments [Snake] do not conform to method getName's

type parameter bounds [A <: AnimalWithLegs]

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

^

<console>:15: error: type mismatch;

found : Snake

required: A

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

^

This is because the type Snake does not extend AnimalWithLegs. (At least not in my world.)

Technical matters: ‘A’ has an “upper bound”

Technically what’s happening here is that I’m defining A with an “upper bound.” Bounds let you place restrictions on type parameters, and in this example I’m saying, “A must be a subtype of the type AnimalWithLegs”:

def getName[A <: AnimalWithLegs](a: A): String = a.name

More generally, this is how you say, “A must be a subtype of B”:

I write more about this topic in, An introduction to Scala Types, so please see that article for a few more details.

A “bounds” video

If you’re interested in more information on this topic, see my free “Scala 3 Bounds” training video.