Highly-rated Functional Programming book

I’m glad to report that my book, Learn Functional Programming The Fast Way, is five-star rated on Gumroad.com. And as I write this sentence on September 6, 2024, it’s also FREE!

I’m glad to report that my book, Learn Functional Programming The Fast Way, is five-star rated on Gumroad.com. And as I write this sentence on September 6, 2024, it’s also FREE!

Scala 3 FAQ: What are opaque types in Scala?

I previously wrote a little about Opaque Types in Scala 3, and today, as I’m working on a new video about opaque types, I thought I’d add some more information about them.

As a quick note to self, I wrote this Scala code as a way to (a) find the first element in a sequence, and then (b) return that element without traversing the rest of the sequence.

I initially thought about writing this code with a while loop, for loop, or for expression — because I knew I needed a loop and a way to break out of a loop — but then I realized that an iterator would help me out here.

Also, please note that there is a potentially-better solution after this — the one that uses the “view.”

So without any further ado, here’s this solution:

This is an excerpt from the Scala Cookbook (partially modified for the internet). This is Recipe 20.3, “Scala best practice: Think "Expression-Oriented Programming".”

You’re used to writing statements in another programming language, and want to learn how to write expressions in Scala, and the benefits of the Expression-Oriented Programming (EOP) philosophy.

Because functional programming is like algebra, there are no null values or exceptions in FP code. But of course you can still have exceptions when you try to access servers that are down or files that are missing, so what can you do? This lesson demonstrates the techniques of functional error handling in Scala.

NOTE: This is a chapter from my book, Learn Scala 3 The Fast Way. Due to a mistake, this lesson was not included in the book.

When you write functions, things can go wrong. In other languages you might throw exceptions or return null values, but in Scala you don’t do those things. (Technically you can, but other people won’t be happy with your code.)

Instead what we do is work with error-handling data types. To demonstrate this I’ll create a function to convert a String to an Int.

If you like Scala 3 opaque types, check out Kit Langton’s Neotype project as a BIG improvement to opaque types. Neotype gets rid of the opaque types verbose boilerplate code, and offers many more improvements that you’ll like as you use this feature more often.

(Or, for more information about them, see my free “Opaque Types in Scala 3” training video.)

This is an excerpt from the Scala Cookbook, 2nd Edition. This is Recipe 23.9, Simulating Dynamic Typing with Union Types.

When using Scala 3, you have a situation where it would be helpful if a value could represent one of several different types, without requiring those types to be part of a class hierarchy. Because the types aren’t part of a class hierarchy, you’re essentially declaring them in a dynamic way, even though Scala is a statically-typed language.

As a “note to self” about using ZIO 2, here are a few ZIO examples that show the ZIO.fail, ZIO.succeed, ZIO.attempt, orElseFail, and orDie methods and functions.

Before looking at the following code, it’s important to know that it uses the following Scala 3 enum:

When I first saw Scala generic type and multiple-parameter group code like this ~12 years ago, my initial thought was, “Wow, maybe I need to think about a different career”:

def race[A, B](lh: IO[A], rh: IO[B])(implicit cs: ContextShift[IO]): IO[Either[A, B]]

But in the end, as Rocky once said, it ain’t so bad. :)

Here are a few nice blog posts on functional error-handling in Scala:

Note: This is an excerpt from my book, Functional Programming, Simplified. (No one has reviewed this text yet. All mistakes are definitely my own.)

It’s surprisingly hard to find a consistent definition of functional programming. As just one example, some people say that functional programming (FP) is about writing pure functions — which is a good start — but then they add something else like, “The programming language must be lazy.” Really? Does a programming language really have to be lazy (non-strict) to be FP? (The correct answer is “no.”)

I share links to many definitions at the end of this lesson, but I think you can define FP with just two statements:

I originally wrote a long introduction to this tutorial about how to work with the Scala Option/Some/None classes, but I decided to keep that introduction for a future article. For this article I’ll just say:

null valuesOption, Some, and Nonematch expressions to handle Option valuesmatch expressions tend to be verbosemap, filter, fold, and many others are the cure for that verbosityGiven that background, the purpose of this article is to show how to use HOFs rather than match expressions when working with Option values.

This is an excerpt from the Scala Cookbook, 2nd Edition. This is Recipe 24.7, Building Modular Systems with Scala 3.

You’re familiar with Martin Odersky’s statement that Scala developers should use “functions for the logic, and objects for the modularity,” so you want to know how to build modules in Scala.

This page contains a large collection of examples of how to use the methods on the Scala List class.

The List class is an immutable, linear, linked-list class. It’s very efficient when it makes sense for your algorithms to (a) prepend all new elements, (b) work with it in terms of its head and tail elements, and (c) use functional methods that traverse the list from beginning to end, such as filter, map, foldLeft, reduceLeft.

In today’s installation of “how to have fun with Scala,” if you want to (a) define a Scala method that takes an input parameter, and (b) that parameter has a generic type, and (c) you further want to further declare that the parameter must extend some base type, then (d) use this “bounds” syntax:

def getName[A <: RequiredBaseType](a: A) = ???

This example can be read as, “The parameter a has the generic type A, and A must be a subtype of RequiredBaseType.”

As a concrete example of how using bounds works, start with a simple base type, such as this Scala trait:

trait SentientBeing {

def name: String

}

Next, extend that base trait with a few more traits:

trait AnimalWithLegs extends SentientBeing

trait TwoLeggedAnimal extends AnimalWithLegs

trait FourLeggedAnimal extends AnimalWithLegs

Then extend those with some concrete case classes:

case class Dog(name: String) extends FourLeggedAnimal

case class Person(name: String, age: Int) extends TwoLeggedAnimal

case class Snake(name: String) extends SentientBeing

Notice that Snake extends SentientBeing, but not AnimalWithLegs.

Now that you have all the types you need, define a method that takes a parameter that has a generic type that must extend some base type. To see how everything works, define it this way the first time:

def getName[A <: SentientBeing](a: A): String = a.name

Because the base type (or “super type”) is SentientBeing, all of these calls work just fine:

getName(Person("Fred", 20))

getName(Dog("Rover"))

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

(Copy and paste those into the Scala REPL if you want to verify they work as advertised.)

Next, change getName so the generic type A must be a subtype of AnimalWithLegs:

def getName[A <: AnimalWithLegs](a: A): String = a.name

Now, when you run the same three method calls again, you’ll see that the Snake example fails because it doesn’t extend AnimalWithLegs:

getName(Person("Fred", 20))

getName(Dog("Rover"))

getName(Snake("Noodles")) //error

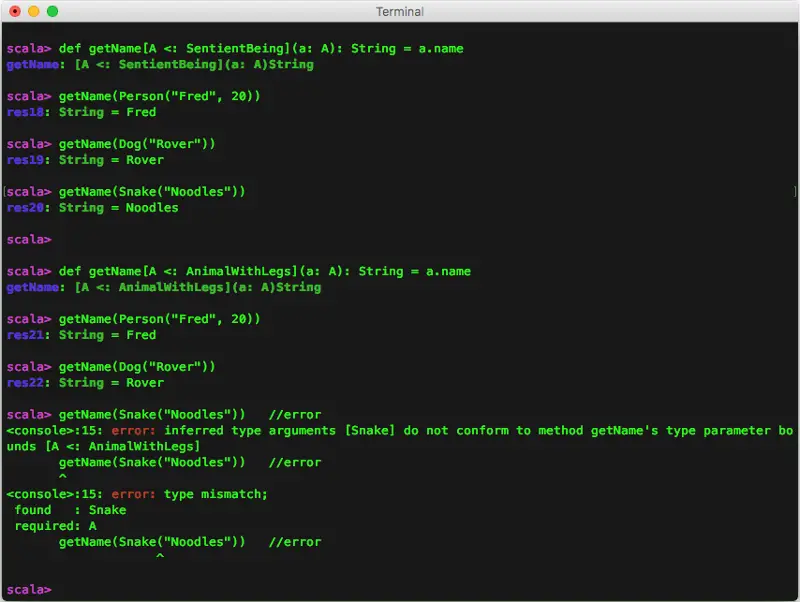

Here’s what the two sets of getName examples look like in the Scala REPL:

(Right-click that image and select “View image” to see it larger.)

As shown, the second Snake example results in this error message:

scala> getName(Snake("Noodles"))

<console>:15: error: inferred type arguments [Snake] do not conform to method getName's

type parameter bounds [A <: AnimalWithLegs]

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

^

<console>:15: error: type mismatch;

found : Snake

required: A

getName(Snake("Noodles"))

^

This is because the type Snake does not extend AnimalWithLegs. (At least not in my world.)

Technically what’s happening here is that I’m defining A with an “upper bound.” Bounds let you place restrictions on type parameters, and in this example I’m saying, “A must be a subtype of the type AnimalWithLegs”:

def getName[A <: AnimalWithLegs](a: A): String = a.name

More generally, this is how you say, “A must be a subtype of B”:

A <: B

I write more about this topic in, An introduction to Scala Types, so please see that article for a few more details.

If you’re interested in more information on this topic, see my free “Scala 3 Bounds” training video.

Here’s an example of Union Types in Scala 3 (Dotty). This image comes from this Martin Odersky video.

UPDATE: For more information, see my free “Scala 3 Union Types” video.

As a brief note today, here’s an example of making an HTTP GET request using ZIO 2 and the Scala sttp library. I also let the user specify a “timeout” value, so the request will timeout, rather than hanging.

As a very important note, this is a blocking approach, not a non-blocking approach.

Here’s the source code and Scala 3 + ZIO 2 + sttp function:

ZIO FAQ: How do I create a very simple ZLayer in a ZIO 2 application?

As a wee bit of background, the ZIO Zlayer approach provides several important purposes, including: