The main goals for this Scala/FP lesson are:

- Discuss the differences between

valanddef“functions” in Scala - Demonstrate the differences between

valanddef“functions”

Background

For the most part — maybe 98% of the time — the differences between defining a “function” in Scala using def or val aren’t important. As I can personally attest, you can write Scala code for several years without knowing the differences. As long as you’re able to define a val function or def method like this:

val isEvenVal = (i: Int) => i % 2 == 0 // a function

def isEvenDef(i: Int) = i % 2 == 0 // a method

and then pass them into the filter method of a List, like this:

scala> val xs = List(1,2,3,4)

xs: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> xs.filter(isEvenVal) //val

res0: List[Int] = List(2, 4)

scala> xs.filter(isEvenDef) //def

res1: List[Int] = List(2, 4)

the differences between them rarely seem to matter.

But as you become a more advanced Scala developer — and as you see the code that some Scala/FP developers like to write — knowing the differences between val functions and def methods can be helpful, and in some cases it may be essential to understand how code works.

`case` expressions in functions

One example of where this is essential is when Scala/FP developers use case expressions to define functions, like this:

val f: (Any) => String = {

case i: Int => "Int"

case d: Double => "Double"

case _ => "Other"

}

When I saw code like this for the first time I thought, “How can that possibly work? There’s no match before the case statements, and the definition also don’t show any input parameters defined ... how can this work?”

The answer is that this function does compile and it does work, yielding the results that you’d expect from the case expressions:

f(1) // Int

f(1d) // Double

f(1f) // Other

f("a") // Other

But why this works can be a mystery — a mystery I’ll resolve in this lesson.

Terminology in this lesson

While def is technically used to define a method, in this section I’ll often refer to it as a function. Furthermore, I’ll use the terms “function created with val” and “function created with def” — or more concisely, “val function” and “def function” — when I want to be clear about what I’m referring to.

A quick summary of the differences between `val` and `def` functions

To get started, here’s a quick summary of the differences between val and def functions.

`val` functions

There are a few different ways you can write a val function, but a common way to write them looks like this:

val add = (a: Int, b: Int) => a + b

A val function has these attributes:

- It is 100% correct to use the term “function” when referring to it.

addis created as a variable, in this case as avalfield.- Under the hood, the Scala compiler implements this specific example as an instance of the

Function2trait. valfunctions are concrete instances ofFunction0throughFunction22.- Because

valfunctions are instances ofFunction0throughFunction22, there are several methods available on these instances, includingandThen,compose, andtoString. - As shown earlier,

valfunctions can usecaseexpressions without a beginningmatch.

Note that you can manually define functions using syntax like this:

val sum = new Function2[Int, Int, Int] { ...

That’s rarely done, but I’ll fully demonstrate that syntax later in this lesson so you can learn more about how things work under the covers.

Because add is a true variable (a val field), you can examine it in the REPL, like this:

scala> add

res0: (Int, Int) => Int = <function2>

Note that the add function isn’t invoked; the REPL just shows its value.

`def` functions

What I call a “def function” looks like this:

def add(a: Int, b: Int) = a + b

It has these attributes:

- It is not 100% correct to use the term “function” when referring to it. Technically, it is not a function.

- It is a method that needs to be defined within a

classorobject. - As a method in a class:

- It has access to the other members in the same class.

- It’s passed an implicit reference to the class’s instance. (For example, when the

mapmethod is called on aList,maphas an implicit reference to thethisobject, so it can access the elements in the instance’sList.)

-

When you write a

def, you can specify parameterized (generic) types, like this:def foo[A](a: A): String = ???

Finally, note that when you define add like this in the REPL:

def add(a: Int, b: Int) = a + b

you can’t examine its value in the REPL in the same way you could with a val function:

scala> add

<console>:12: error: missing arguments for method add;

follow this method with `_' if you want to treat it as a

partially applied function

add

^

Converting methods to functions

As a final note in this initial summary, you can convert a def method into a real val function. You can do this manually yourself, and the Scala compiler also does it automatically when needed. This feature is called, “Eta Expansion,” and I show how it works in another appendix in this book.

More details

I’ll show many more details in this lesson — for instance, I’ll show decompiled examples of val and def functions — but I wanted to start with these key points.

Why a `val` function can use a `case` expression without a beginning `match`

I noted at the beginning of this lesson that you can write a val function using case expressions without a beginning match keyword, like this:

val f: (Any) => String = {

case i: Int => "Int"

case d: Double => "Double"

case _ => "Other"

}

The reasons this syntax works are:

- A block of code with one or more

caseexpressions is a legal way to define an anonymous function. - As I mention in the “Functions are Values” lesson, when you create a

valfunction, all you’re really doing with code like this is assigning a variable name to an anonymous function.

To support that first statement, Section 15.7 of Programming in Scala states:

“A sequence of cases in curly braces can be used anywhere a function literal can be used.”

Here are two examples that show how you can use a case expression as an anonymous function. First, a modulus example:

scala> List(1,2,3,4).filter({ case i: Int => i % 2 == 0 })

res0: List[Int] = List(2, 4)

Next, a “string length” example:

scala> val misc = List("adam", "alvin", "scott")

misc: List[String] = List(adam, alvin, scott)

scala> misc.map({ case s: String => s.length > 4 })

res1: List[Boolean] = List(false, true, true)

If you read the 1st Edition of the Scala Cookbook, you may also remember this example from Section 9.8 on Partial Functions:

scala> List(0,1,2) collect { case i: Int if i != 0 => 42 / i }

res2: List[Int] = List(42, 21)

This example works because (a) the case expression creates an anonymous function, and (b) the collect method works with Partial Functions. Contrast that with map, which explodes with a MatchError when it’s used with that same case expression:

scala> List(0,1,2) map { case i: Int if i != 0 => 42 / i }

scala.MatchError: 0 (of class java.lang.Integer)

The `val` function syntax

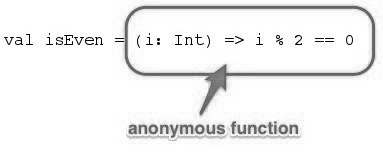

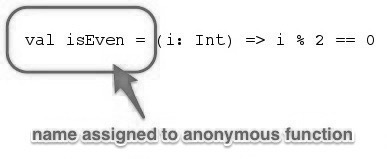

As I noted earlier, a val function is simply a variable name that’s assigned to a function literal. To demonstrate this, here’s the function literal:

And here’s the variable name being assigned to the function literal:

By contrast, if you want to write the same code using def, it would be defined like this:

def isEven(i: Int): Boolean = i % 2 == 0

Decompiling a `def` method

As you might suspect, a def method in a Scala class is compiled into a similar method on a Java class. To demonstrate this, if you start with this Scala class:

class DefTest {

def add1(a: Int) = a + 1

}

you can then compile it with scalac. When you compile it with the following command and look at its output, you’ll find that there’s still a method in a class:

$ scalac -Xprint:all DefTest.scala

package <empty> {

class DefTest extends Object {

def add1(a: Int): Int = a.+(1); //<-- the method

def <init>(): DefTest = {

DefTest.super.<init>();

()

}

}

}

If you further disassemble the resulting .class file with javap, you’ll see this output:

$ javap DefTest

Compiled from "DefTest.scala"

public class DefTest {

public int add1(int); //<-- the method

public DefTest();

}

Clearly, add1 is a method in the bytecode for the DefTest class.

Finally, if you completely decompile the .class file back into Java source code using Jad, you’ll again see that add1 is a method in the Java version of the DefTest class:

public class DefTest {

public int add1(int a) {

return a + 1;

}

public DefTest() {}

}

By all accounts, creating a Scala def method creates a standard method in a Java class.

Decompiling a `val` function

A Scala function that’s created with val is very different than a method created with def. While def creates a method in a class, a function is an instance of a class that implements one of the Function0 through Function22 traits.

To see this, create a class named ValTest.scala with these contents:

class ValTest {

val add1 = (a: Int) => a + 1

}

When you compile that class with scalac, you’ll see that it creates two .class files:

ValTest.class

ValTest$$anonfun$1.class

When you decompile ValTest.class with javap you see this output:

$ javap ValTest

Compiled from "ValTest.scala"

public class ValTest {

public scala.Function1<java.lang.Object, java.lang.Object> add1();

public ValTest();

}

That output shows that add1 is defined as a method in the ValTest class that returns an instance of the Function1 trait.

Back in the good old days (around Scala 2.8) it was much easier to look at this code to see what’s going on, but these days I find it hard to see what’s going on in these class files using javap, so I revert to decompiling them with Jad. Decompiling ValTest.class converts the class file to Java source code:

import scala.Function1;

import scala.Serializable;

import scala.runtime.BoxesRunTime;

public class ValTest {

public Function1 add1() {

return add1;

}

public ValTest() {}

private final Function1 add1 = new Serializable() {

public final int apply(int a) {

return apply$mcII$sp(a);

}

public int apply$mcII$sp(int a) {

return a + 1;

}

public final volatile Object apply(Object v1) {

return

BoxesRunTime.boxToInteger(apply(BoxesRunTime.unboxToInt(v1))); }

public static final long serialVersionUID = 0L;

}

;

}

While this code is still hard to interpret, a couple of things are clear:

add1()is a method in theValTestclass.- The

add1()method returns theadd1instance. - The

add1instance is created by making an anonymous class instance ofscala.Serializable. - The

add1instance has anapplymethod that calls another method namedapply$mcII$sp, and that second method contains the body of the original function,a + 1.

What isn’t clear from this code unless you dig pretty deep into it is that the original Scala function:

val add1 = (a: Int) => a + 1

creates add1 as an instance of Function1. It’s easier to see this in the REPL.

Looking at `val` functions in the REPL

When you put this function in the Scala REPL, you see this result:

scala> val add1 = (a: Int) => a + 1

add1: Int => Int = <function1>

This shows that add1 is an instance of Function1. If you’re not comfortable with the REPL output, one way you can prove this is to show that add1 is an object with an apply method:

scala> add1.apply(2)

res0: Int = 3

To be clear, when you call add1(2), this is exactly what happens under the hood. Scala has some nice syntactic sugar that hides this from you — and makes your code easy to read — but this is what really happens under the hood.

You can further demonstrate this by looking at the Function1 Scaladoc. There you’ll see that any class that implements Function1 must have these three methods:

andThencomposetoString

This code demonstrates that add1 has the andThen method:

scala> (add1 andThen add1)(5)

res1: Int = 7

This shows that compose is available on add1:

scala> (add1 compose add1)(10)

res2: Int = 12

toString also works:

scala> add1.toString

res3: String = <function1>

Finally, because add1 takes an Int input parameter and returns an Int, it is implemented as an instance of Function1[Int,Int]. You can also demonstrate this in the REPL:

scala> add1.isInstanceOf[Function1[Int,Int]]

res4: Boolean = true

Clearly, add1 is an object of type Function1.

Trying that on a `def` method

By comparison, if you try to call toString on a method created with def, all you get is an error:

scala> def double(a: Int) = a * 2

double: (a: Int)Int

scala> double.toString

<console>:12: error: missing arguments for method double;

follow this method with `_' if you want to treat it as a

partially applied function

double.toString

^

As mentioned, a def is not really a val, it just works like a val when you pass it to other functions because of the Eta Expansion feature that I mentioned earlier.

Creating `Function` instances manually

As a final way of showing that a function created with val creates a complete object, it may help to know that you can create your own Function1, Function2 ... Function22 instances manually. This gives you another idea of how things work under the hood.

Previously I defined an add1 function like this:

val add1 = (a: Int) => a + 1

Then I showed that it looks like this in the REPL:

scala> val add1 = (a: Int) => a + 1

add1: Int => Int = <function1>

The following code shows the manual way to create a similar function:

class Add2 extends Function1[Int, Int] {

def apply(a: Int) = a + 2

}

val add2 = new Add2

Once you’ve taken those steps, you can invoke add2 just like add1:

add2(1)

Because add2 takes an Int and returns an Int, it’s implemented as an instance of Function1[Int,Int]. Had it been a function that took a Double and returned a String, it would be defined as a Function1[Double,String].

If a function takes two input parameters, you define it as an instance of

Function2, a function with three input parameters is an instance ofFunction3, etc.

If you copy and paste those add2 lines of code into the REPL, you’ll see this output, which confirms that it works as described:

defined class Add2

add2: Add2 = <function1>

res0: Int = 3

Using the anonymous class syntax

You can also manually create a function using the anonymous class syntax. Here’s a Function2 instance named sumLengths that adds the lengths of two strings you provide:

val sumLengths = new Function2[String, String, Int] {

def apply(a: String, b: String): Int = a.length + b.length

}

The REPL shows that it works as expected:

scala> sumLengths("talkeetna", "alaska")

res0: Int = 15

In practice I don’t create functions like this, but it can be helpful to know some of the things that the Scala compiler does for you.

Using parameterized (generic) types

One thing you can do with def methods that you can’t do with val functions is use generic types. That is, with def you can write a function that takes a generic type A, like this:

def firstChar[A](a: A) = a.toString.charAt(0)

and then use it as shown in these examples:

firstChar("foo")

firstChar(42)

You can’t do the same thing with the simple val function syntax:

// error: this won't compile

val firstChar[A] = (a: A) => a.toString.charAt(0)

Coerce a parameterized method into a function

You can coerce a parameterized method into a function. For example, start with a method that uses a generic type:

def lengthOfThing[A] = (a: A) => a.toString.length

Then coerce that method into a function as you declare a specific type:

val f = lengthOfThing[Int]

Once you do that, you can call the function f you just created:

f(694)

This works, as shown in the REPL:

scala> def lengthOfThing[A] = (a: A) => a.toString.length

lengthOfThing: [A]=> A => Int

scala> val f = lengthOfThing[Int]

f: Int => Int = <function1>

scala> f(694)

res0: Int = 3

Kinda-sorta use generic types with `FunctionX` traits

Digging deeper into the magic toolbox ... you can more or less do the same thing by using parameterized types with the FunctionX traits, like this Function2 example:

class SumLengths[A, B] extends Function2[A, B, Int] {

def apply(a: A, b: B): Int =

a.toString.length + b.toString.length

}

Once you’ve defined that class, you can create a sumLengths instance like this:

val sumLengths = new SumLengths[Any, Any]

sumLengths("homer", "alaska")

If you paste the class and those last two lines into the REPL, you’ll see this output:

defined class SumLengths

sumLengths: SumLengths[Any,Any] = <function2>

res0: Int = 11

Note that some of these examples aren’t very practical; I just want to show some things that can be done.

| this post is sponsored by my books: | |||

#1 New Release |

FP Best Seller |

Learn Scala 3 |

Learn FP Fast |

Summary

In summary, this lesson showed the differences between val functions and def methods. Some of the topics that were covered are:

- Using

caseexpressions withvalfunctions and anonymous classes without requiring the leadingmatch - A

defmethod is a method in a class (just like a Java method is a method in its class) valfunctions are a concrete instances of Function0 through Function22valfunctions are objects that have methods likeandThenandcompose- How to manually define

valfunctions

See also

- Much of this discussion was inspired by Jim McBeath’s article, Scala functions vs methods

- Function composition (

andThen,compose) - Stack Overflow has a discussion titled, Difference between method and function in Scala, which builds on Mr. McBeath’s blog post

- How much one ought to know about Eta Expansion

- Revealing the Scala magician’s code: method vs function

- An old scala-lang.org post, Passing methods around

- The best book on Scala and functional programming I know :)