“Folds can be used to implement any function where you traverse a list once, element by element, and then return something based on that. Whenever you want to traverse a list to return something, chances are you want a fold. That’s why folds are, along with maps and filters, one of the most useful types of functions in functional programming.”

Source code

The source code for this Scala lesson is available at the following URL:

Goal

The primary goal of this lesson is to show that while recursion is cool, fun, and interesting, with Scala methods like filter, map, fold, and reduce, you won’t need to use recursion as often as you think. As just one example of this, if you find yourself writing a recursive function to walk over all of the elements in a list to return some final, single value, this is a sign that you may want to use fold or reduce instead.

Introduction

As you saw in the lessons on recursive programming, you can use recursion to solve “looping” programming problems in a functional way. Hopefully you also saw that recursion isn’t too hard, and might even be fun.

So, while recursion is great, as a functional programmer you also need to know that you won’t need to use it as often as you might think. When you’re working with Scala collections it’s often easier to use built-in collection methods that take care of the recursion for you. Some of the most common methods you’ll use are:

filtermapreducefold

This lesson shows how to use built-in collections methods like reduce, fold, and scan, so you can use them instead of writing custom recursion functions.

Calculating a sum with recursion

As a quick review, in the recursion lessons you saw that if you have a List like this:

val list = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

you can write a recursive function to calculate the sum of the list elements like this:

def sum(list: List[Int]): Int = list match {

case Nil => 0

case x :: xs => x + sum(xs)

}

This function isn’t tail-recursive, but it’s simpler than the tail-recursive sum function, so I’ll use it in this lesson.

As a quick review, you can read this function — the second case statement in particular — as, “The sum of a List is (a) the value of the first element plus (b) the sum of the remaining elements.” Also, because the last element in a Scala List is the Nil value, you write the first case condition to end the recursion (and return from it) when that last element is reached.

That’s nice, but ...

That recursive sum function is awesome, but if you look closely at a product algorithm, you’ll begin to see a pattern:

def product(list: List[Int]): Int = list match {

case Nil => 1

case x :: xs => x * product(xs)

}

Do you see the pattern?

If not, see if you can find the pattern by filling in the blanks in the following code:

def ALGORITHM(list: List[Int]): Int = list match {

// this case always handles what?

case ___________

// this case always seems to have a head, tail, and <something else>

case ____ :: ____ => ____ ________ ALGORITHM(____)

}

I probably didn’t give you enough hints of what I’m looking for, so I’ll give you my solution. When you look at sum and product in a general sense, the pattern I see looks like this:

def ALGORITHM(xs: List[Int]): Int = xs match {

case [TERMINATING CONDITION]

case HEAD :: TAIL => HEAD [OPERATOR] ALGORITHM(TAIL)

}

Because there’s a set of commonly-needed recursive algorithms — and because programmers don’t like writing the same code over and over — these algorithms have been encapsulated as methods in the Scala collections classes. The great thing about this is that you can use these existing methods instead of having to write custom recursive functions manually each time.

In the case of the sum and product algorithms I just showed, this general pattern is encapsulated as a series of “reduce” functions in the collections classes. I’ll demonstrate those next.

Using reduce

While the reduce method on the Scala List class isn’t implemented exactly as I showed in the sum and product functions, it does encapsulate the same basic algorithm: walk through a sequence of elements, apply a function to each element, and then return a final, single value. As a result, you can use reduce instead of custom recursive algorithms, like the sum and product functions.

At the time of this writing, the

Listclassreducemethod is implemented in the TraversableOnce trait. If you look at the source code for that class, you’ll see thatreducecallsreduceLeft, so you’ll want to pay attention to thereduceLeftsource code.

When you first use reduce it may look a little unusual, but you’ll quickly get used to it, and eventually appreciate it.

How to calculate a sum with reduce

To use reduce on a Scala sequence, all you have to do is provide the algorithm you want reduce to use. For example, a “sum” algorithm using reduce looks like this:

def sum(list: List[Int]): Int = list.reduce(_ + _)

If you’ve never used reduce before, that _ + _ code may look a little unusual at first, but it’s just an anonymous function. It may also be easier to read if I show the long form for the anonymous function:

def sum(list: List[Int]): Int = list.reduce((x,y) =>

x + y

)

A key here is knowing that reduce passes two variables to the anonymous function. I’ll explain these variables more in the next section.

Until then, a quick example in the Scala REPL demonstrates that this approach works as a “sum the elements in a list” algorithm:

scala> def sum(list: List[Int]): Int = list.reduce((x,y)

=> x + y)

sum: (list: List[Int])Int

scala> val a = List(1,2,3,4)

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> sum(a)

res1: Int = 10

Cool, right?

Let’s take a look at how reduce works.

How reduce works

The reduce method in Scala is implemented as a little wrapper method that calls the reduceLeft method, so I’ll describe how reduceLeft works first. After that I’ll show how reduceRight works.

Have no fear about those names.

reduceLeftsimply walks a collection from the first element to the last element (from the left to the right), andreduceRightdoes the opposite thing, walking the collection from the last element backwards to the first element.

How reduceLeft works

When you use reduceLeft to walk through a sequence, it walks the sequence in order from its first element (the head element) to the last element. For instance, if a sequence named friends has four elements, reduceLeft first works with friends[0], then friends[1], then friends[2], and finally friends[3].

More accurately, what reduceLeft does is:

- It applies your algorithm to the first two elements in the sequence. In the first step it applies the algorithm to

friends[0]andfriends[1]. - Applying your algorithm to those two elements yields a result.

- Next,

reduceLeftapplies your algorithm to (a) that result, and (b) the next element in the sequence (friends[2], in this case). That yields a new result. reduceLeftcontinues in this manner for all elements in the list.- When

reduceLeftfinishes running over all of the elements in the sequence, it returns the final result as its value. For example, asumalgorithm returns the sum of all of the elements in a list as a single value, and aproductalgorithm returns the product of all list elements as a single value.

As you can imagine, this is where the name “reduce” comes from — it’s used to reduce an entire list down to some meaningful, single value.

One subtle but important note about reduceLeft: the function you supply must return the same data type that’s stored in the collection. This is necessary so reduceLeft can combine (a) the temporary result from each step with (b) the next element in the collection.

Demonstrating how reduceLeft works

Next, I’ll demonstrate how reduceLeft works in two ways. First, I’ll add some “debug/trace” code to an algorithm so you can see output from reduceLeft as it runs. Second, I’ll show a handy diagram I use when I apply reduceLeft to new algorithms.

1) Showing how reduceLeft works with debug/trace code

A good way to show how reduceLeft works is to put some debugging println statements inside an algorithm. I’ll use a modified version of the sum function I showed earlier to demonstrate this.

First, I’ll define an add function that produces debug output:

def add(x: Int, y: Int): Int = {

val theSum = x + y

println(s"received $x and $y, their sum is $theSum")

theSum

}

All this function does is add two integers, but before it returns its result it prints out information that will help demonstrate how reduceLeft works.

Now all I have to do is use this add function with some sample data. This is what it looks like when I use add with reduceLeft on a simple List[Int]:

scala> val a = List(1,2,3,4)

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> a.reduceLeft(add)

received 1 and 2, their sum is 3

received 3 and 3, their sum is 6

received 6 and 4, their sum is 10

res0: Int = 10

This output shows:

- The first time

addis called byreduceLeftit receives the values1and2. It yields the result3. - The second time

addis called it receives the value3— the result of the previous application — and3, the next value in the list. It yields the result6. - The third time

addis called it receives the value6— the result of the previous application — and4, the next value in the list. It yields the result10. - At this point

reduceLefthas finished walking over the elements in the list and it returns the final result,10.

Exercise

Write down what the reduceLeft output looks like if you change the add algorithm to a product algorithm:

scala> a.reduceLeft(product)

received __ and __, their product is ____

received __ and __, their product is ____

received __ and __, their product is ____

res0: Int = ____

Exercise

reduceLeft is flexible, and can be used for any purpose where you need to walk through a sequence in the manner described to yield a final, single result. For instance, this function yields the largest of the two values it’s given:

def max(a: Int, b: Int) = {

val max = if (a > b) a else b

println(s"received $a and $b, their max is $max")

max

}

Exercise: Given this new list:

val xs = List(11, 7, 14, 9)

write down what the output looks like when you use max with reduceLeft on that list:

scala> xs.reduceLeft(max)

received __ and __, their max is ____

received __ and __, their max is ____

received __ and __, their max is ____

res0: Int = ____

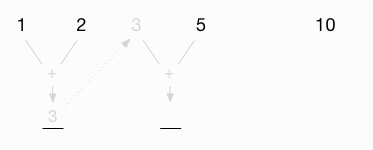

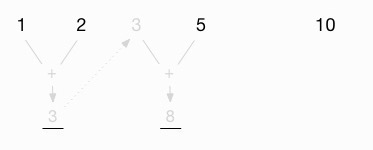

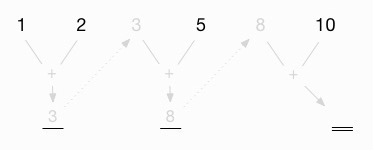

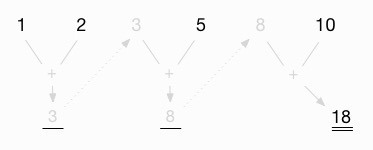

2) Showing how reduceLeft works with diagrams

Whenever I forget how Scala’s “reduce” functions work, I come back to a simple diagram that helps remind me of how the process works.

To demonstrate it, I’ll start with this list of values:

val a = List(1, 2, 5, 10)

Then I’ll imagine that I’m using the add function with reduceLeft on that list:

a.reduceLeft(add)

The first thing I do is write out the first several values of the list in a row, like this:

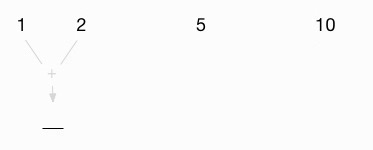

I leave spaces between the values because my next step involves hand-calculating the result of applying my algorithm to the first two elements of the list:

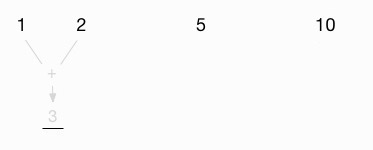

This shows that I’m using a + algorithm, and in its first step, reduceLeft applies that algorithm to the first two values in the list, 1 and 2. This yields the first intermediate result, 3:

The next thing I do is carry this intermediate value up to the space between the original 2 and 5 in the list:

Then I add this intermediate value (3) to the next value, 5:

This gives me a new intermediate value of 8:

Now I proceed as before, carrying that value back to the top, between the original 5 and 10:

Finally, I add this intermediate value (8) to the last value in the list (10) to get the final result, 18:

For me, this is a nice way of visualing how the reduceLeft function works. When I haven’t used it for a while, I find that it helps to see a diagram like this.

Exercises

1) Using the same list values, draw the “product” algorithm:

2) Using the same list values, draw the “max” algorithm:

Summary of the visual diagram

In summary, this diagram is a visual way to show how reduceLeft works. The generic version of the diagram looks like this:

A look at a different data type

The data type contained in the sequence you’re working on can be anything you need. For instance, if you want to determine the longest or shortest string in a list of strings, you can use reduceLeft with the length method of the String class.

To demonstrate this, start with a sequence of strings:

val peeps = Vector(

"al", "hannah", "emily", "christina", "aleka"

)

Then you can determine the longest string like this:

scala> peeps.reduceLeft((x,y) => if

(x.length > y.length) x else y)

res0: String = christina

and the shortest string like this:

scala> peeps.reduceLeft((x,y) => if

(x.length < y.length) x else y)

res1: String = al

You can also create functions like longest and shortest:

def longest(x: String, y: String) =

if (x.length > y.length) x else y

def shortest(x: String, y: String) =

if (x.length < y.length) x else y

and use them to get the same results:

scala> peeps.reduceLeft(longest)

res0: String = christina

scala> peeps.reduceLeft(shortest)

res1: String = al

If this had been a collection of Person instances, you could run a similar algorithm on each person’s name to get the longest and shortest names.

As another example, you can concatenate a list of strings using the same approach I used to sum the elements in a list:

scala> val x = List("foo", "bar", "baz")

x: List[String] = List(foo, bar, baz)

scala> x.reduceLeft(_ + _)

res0: String = foobarbaz

reduceRight

The reduceRight method works like reduceLeft, but it marches through the elements in order from the last element to the first element. For summing the elements in a List[Int] the order doesn’t matter:

scala> val a = List(1,2,3,4)

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> a.reduceLeft(_ + _)

res1: Int = 10

scala> a.reduceRight(_ + _)

res2: Int = 10

But if for some reason you want to apply a subtraction algorithm to the same list, it can make a big difference:

scala> val a = List(1,2,3,4)

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> a.reduceLeft(_ - _)

res0: Int = -8

scala> a.reduceRight(_ - _)

res1: Int = -2

How reduceRight receives its elements

To be clear about how reduceRight works, this example shows how it works with the earlier “debug add” function:

scala> val a = List(1,2,3,4)

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

scala> a.reduceRight(add(_,_))

received 3 and 4, their sum is 7

received 2 and 7, their sum is 9

received 1 and 9, their sum is 10

res0: Int = 10

Note that in the first step, reduceRight receives the elements as 3 and 4. When I first learned about it, I assumed that it would receive those elements as 4 and 3 (starting with the last element, then the next-to-last element, etc.). This is an important detail to know.

Note 1: reduce vs reduceLeft

Being one for brevity, I’d prefer to use reduce in my code rather than reduceLeft, assuming that they work the same way. However, that doesn’t appear to be a safe assumption.

Ever since I began looking into it (starting somewhere around 2011), the reduce method in the Scala sequence classes has always just called reduceLeft. This is how the reduce method is defined in the TraversableOnce class in Scala 2.12.2:

def reduce[A1 >: A](op: (A1, A1) => A1): A1 =

reduceLeft(op)

That being said, there appears to be no guarantee that this will always be the case. The documentation for the reduce method in the List class Scaladoc states, “The order in which operations are performed on elements is unspecified and may be nondeterministic.” As a result, I always use reduceLeft when I want to walk a collection from its first element to its last.

In the Scala Cookbook I showed that

reduceis definitely not deterministic when using the parallel collections classes.

Note 2: Performance

In theory, if your algorithm is commutative — changing the order of the operands does not change the result, such as + and * — you can use reduceLeft or reduceRight to get the same result.

In practice, my tests are different than theory. In one example, using Scala 2.12 with the default JVM parameters, when I create a Vector that contains ten million random Int values, xs.reduceLeft(max) is consistently at least three times faster than xs.reduceRight(max).

Microbenchmarks like this are notoriously criticized, but a difference of 3-4X is significant. You can test this on your own system with the

ReducePerformanceTest1application in this lesson’s source code.

Furthermore, if (a) you’re specifically working with a Scala List and (b) your algorithm is commutative, you should always use reduceLeft. This is because List is a linear sequential collection — not an indexed sequential collection — so it will naturally be faster for an algorithm to work from the head of a List towards the tail. (A Scala List is a singly linked-list, so moving from the head towards the tail of the list is fast and efficient.)

The source code for this lesson shows that the List problem is worse than the previous paragraph suggests. I’ve found that if you’re specifically working with a Scala List you can easily generate a StackOverflowError with a call to reduceRight(max). As you can see in the ReducePerformanceTest1 application source code for this lesson, with the default JVM settings and a List with 30,000 Int values, calling xs.reduceRight(max) throws a StackOverflowError.

In a related note, the reduceRight method attempts to do what it can to be efficient. In the TraversableOnce class in Scala 2.12.2, reduceRight first reverses the list and then calls reduceLeft:

def reduceRight[B >: A](op: (A, B) => B): B = {

if (isEmpty)

throw new

UnsupportedOperationException("empty.reduceRight")

reversed.reduceLeft[B]((x, y) => op(y, x))

}

In that same class, reversed is defined like this:

protected[this] def reversed = {

var elems: List[A] = Nil

self foreach (elems ::= _)

elems

}

See the source code of that class for more information. (And wow, did you notice the use of a var field and a foreach call in reversed, and how it takes no input parameters? There’s no FP in this method.)

In summary, my rules for List are:

- If the function is commutative, use

reduceLeftorreduce - If the function is not commutative, use what you need for your algorithm (

reduceLeftorreduceRight)

Finally, if your algorithm requires you to use reduceRight and you find that there is a performance problem, consider using an indexed sequential collection such as Vector.

If you’re not familiar with the terms linear and indexed in this discussion, I write about them in the Collections lessons in the Scala Cookbook.

How foldLeft works

The foldLeft method works just like reduceLeft, but it lets you set a seed value for the first element. The following examples demonstrate a “sum” algorithm, first with reduceLeft and then with foldLeft, to demonstrate the difference:

scala> val a = Seq(1, 2, 3)

a: Seq[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

scala> a.reduceLeft(_ + _)

res0: Int = 6

scala> a.foldLeft(20)(_ + _)

res1: Int = 26

scala> a.foldLeft(100)(_ + _)

res2: Int = 106

In the last two examples, foldLeft uses 20 and then 100 for its first element, which affects the final sum, as shown.

To further demonstrate how foldLeft works, I’ll go back to the debug add function I used earlier:

def add (x: Int, y: Int): Int = {

val theSum = x + y

println(s"received $x and $y, their sum is $theSum")

theSum

}

Here’s the result of applying add to the last foldLeft example:

scala> val a = Seq(1, 2, 3)

a: Seq[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

scala> a.foldLeft(100)(add)

received 100 and 1, their sum is 101

received 101 and 2, their sum is 103

received 103 and 3, their sum is 106

res0: Int = 106

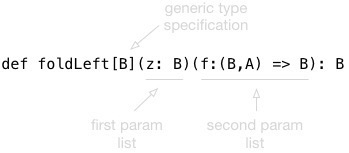

Aside: foldLeft uses two parameter lists

Remember that when you see something like foldLeft(20)(_ + _), it means that foldLeft is defined to take two parameter lists. This is what foldLeft’s signature looks like on Scala’s sequential collection classes:

How foldRight works

The foldRight method works just like reduceRight — working through the sequence in order from the last element back to the first element — and also lets you set a seed value. Here’s an example of how foldRight works with the add function I just showed:

scala> a.foldRight(100)(add)

received 3 and 100, their sum is 103

received 2 and 103, their sum is 105

received 1 and 105, their sum is 106

res0: Int = 106

Again, for algorithms that aren’t commutative, it can be important to notice the order in which the first two elements are supplied to your function.

scanLeft and scanRight

Two methods named scanLeft and scanRight walk through a sequence in a manner similar to foldLeft and foldRight, but the key difference is that they return a sequence rather than a single value.

The scanLeft Scaladoc states, “Produces a collection containing cumulative results of applying the operator going left to right.” To understand how it works, I’ll use the trusty add function again:

def add (x: Int, y: Int): Int = {

val theSum = x + y

println(s"received $x and $y, their sum is $theSum")

theSum

}

Here’s what scanLeft looks like when it’s used with add and a seed value:

scala> val a = Seq(1, 2, 3)

a: Seq[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

scala> a.scanLeft(10)(add)

received 10 and 1, their sum is 11

received 11 and 2, their sum is 13

received 13 and 3, their sum is 16

res0: Seq[Int] = List(10, 11, 13, 16)

A few notes about this:

scanLeftreturns a new sequence, as opposed to the single value thatreduceLeftandfoldLeftreturn.scanLeftis a little likemap, but wheremapapplies a function to each element in a collection,scanLeftapplies a function to (a) the previous result and (b) the current element in the sequence.

As a final note, the scanRight method works the same way, but marches through the collection from the last element backwards to the first element:

scala> a.scanRight(10)(add)

received 3 and 10, their sum is 13

received 2 and 13, their sum is 15

received 1 and 15, their sum is 16

res1: Seq[Int] = List(16, 15, 13, 10)

How foldLeft is like recursion

I mentioned at the beginning of this lesson that you won’t have to use recursion as often as you think because the FP developers who came before us recognized that there are certain common patterns involved in writing recursive functions.

For instance, imagine a world in which all lists contain only three elements, and you want to write a foldLeft function. If you further assume that you’re writing a foldLeft function for only Int values, you can write foldLeft like this:

def foldLeft(a: Int)(xs: List[Int])(f: (Int, Int) => Int):

Int = {

// 1st application

val result1 = f(a, xs(0))

// 2nd application

val result2 = f(result1, xs(1))

// 3rd application

val result3 = f(result2, xs(2))

result3

}

When you look at that code, it sure looks like there’s a pattern there: a recursive pattern at that! In fact, if you rename the input parameter a to result0, the pattern becomes even more obvious:

// 1st iteration

val result1 = f(result0, xs(0))

// 2nd iteration

val result2 = f(result1, xs(1))

// 3rd iteration

val result3 = f(result2, xs(2))

result3

The pattern is:

- Create a result by applying the function

fto (a) the previous result and (b) the current element in the list. - Do the same thing with the new result and the next list item.

- Do the same thing with the new result and the next list item ...

Implementing foldLeft with recursion

I showed how to write recursive code earlier in this book, so at this point I’ll just jump right into a complete example of how to write a foldLeft function for a List[Int] using recursion:

package folding

object FoldLeftInt extends App {

val a = List(1,2,3,4)

def add(a: Int, b: Int) = a + b

println(foldLeft(0)(a)(add))

def foldLeft(lastResult: Int)(list: List[Int])(f: (Int, Int) => Int): Int = list match {

case Nil => lastResult

case x :: xs => {

val result = f(lastResult, x)

println(s"last: $lastResult, x: $x, result = $result")

foldLeft(result)(xs)(f)

}

}

}

I left the debugging println statement in there so you can see this output when you run this program:

last: 0, x: 1, result = 1

last: 1, x: 2, result = 3

last: 3, x: 3, result = 6

last: 6, x: 4, result = 10

10

As this shows, foldLeft and other functions like it are just convenience functions that exist so you don’t have to write the same recursive code over and over again.

Convert foldLeft to use generic types

As I’ve shown throughout this book, I often write functions using a specific type, then convert them to a generic type when I see that the algorithm doesn’t depend on the specific type. The foldLeft algorithm doesn’t depend on the type being an Int, so I can replace all of the Int references in the function signature to A, and then add the required [A] before the function parameter lists:

def foldLeft[A](lastResult: A)(list: List[A])(f: (A, A) => A): A

= list match { ...

Even more methods

There are more methods in the Scala collections classes that work in a similar manner. See the List class Scaladoc for a complete list of the methods that are available for the List class.

Key points

In summary, the goal of this lesson is to demonstrate why you won’t need to write recursive functions as often as you might expect. Built-in Scala collection methods like filter, map, reduce, and fold greatly reduce the number of custom “iterate over this list” functions you’ll need to write.

In fact, if you find yourself writing a recursive function to walk over all of the elements in a list to return some final, single value, this is a sign that you may want to use fold or reduce instead.

| this post is sponsored by my books: | |||

#1 New Release |

FP Best Seller |

Learn Scala 3 |

Learn FP Fast |

See also

- “Fold” on the Haskell Wiki

- “Fold” on Wikipedia

- How to use variable names with foldLeft

- How to walk through a Scala collection with reduce and fold

- The Scala Cookbook intentionally includes over 130 pages of recipes and examples of how to use the Scala collections methods (because it’s valuable to know how they work)